Roberto Dutesco is a multi-faceted artist whose work spans photography, film, poetry and more. From fashion and travel to wild horses, flowers and rocks, Roberto’s work is a visual representation of truth, of beauty, of peace, and of our connection with the larger energy of the universe. He observes and thinks deeply about the ways of nature and the lessons and wisdom to be found all around. Though something of a free spirit, Roberto has always approached and explored art with discipline and a sense of mission. He continually references memories and ideas from his childhood growing up in Romania and carries that with him in his global and never-ending quest to bring a message of unity and peace to the world.

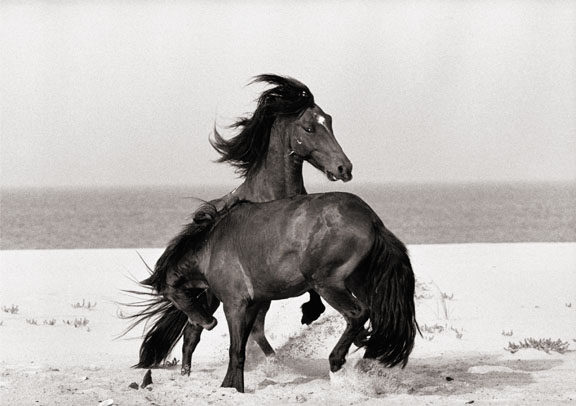

“Love Bite” – Wild Horses of Sable Island series by Roberto Dutesco

You began taking photos with your father’s camera as a child, but you studied painting, sculpture and drawing at the National School of the Arts in Bucharest, and it was another 10 years before you formally studied photography in Montreal. Can you tell me about that moment of discovery and realizing your path forward as a photographer?

The moment forward perhaps may have happened prior to my studies, prior to my moving to Montreal. When I was living in Bucharest, my whole family was enamored with photographs and cameras. My father had an amazing camera, my uncle was a great photographer, my grandfather also took photographs. So it was something I actually grew up with. I grew up with a box of photographs — maybe 500 or more — of my whole family, of my father’s travels through Europe, of many places that he had seen. I remember a picture of him looking at the Mona Lisa, right next to her — of course, you cannot do that anymore. So I grew up with that box, and I remember clearly: I would almost go through a ritual, maybe every other day, and I would look at every single picture and study them and see these places that I knew instinctively I would one day visit. So that box of photographs was the first moment of discovery in realizing my visual world.

My path as a photographer came as a realization quite a bit later, prior to actually studying photography. I moved to Montreal from Bucharest, and I was working in this factory where I was working with complicated diagrams and cables for computers. But it was a simple job for me and came easy. As I was working there, I thought about buying a camera, a Nikon. All of a sudden, excited, I bought a camera on a Friday, and on a Saturday I took the camera on Mount Royal and took pictures of some flowers and of my family. The following week I took some of my photographs to work, excited to show my colleagues how wonderful the spring flowers on Mount Royal were, and one of my colleagues bought one of my photos for $5. So at that moment, all those magazines that were on every single newsstand in Montreal and around the world just showed up in front of my face, and I realized, ‘Wow, somebody must be taking those photographs. Why not me?’ All of a sudden I thought what I have to do in order to become a photographer is study. Because I knew in order to become excellent at anything, you have to have the technical background. Without that technical background, it’s almost impossible to achieve anything, and you always wonder if you’re doing the right thing. And that’s one thing I did not want to do. So that was the actual moment.

Once I decided I was going to become a photographer, I enrolled in Dawson Institute of Photography, a 3 year program. In this program, I was introduced to, at the time, perhaps the best photographer in Montreal. He was a fashion photographer, Barry Harris. He needed an assistant, and I helped him print about 500 photographs almost overnight. By having access to a studio with a top photographer, I switched my studies from day to night. So I would be with Barry Harris the full day as his assistant, then at 5:00 or 6:00 I would go to school. Just by chance, his studio was on the same floor as my school, so I immediately not only had access to all his knowledge and showing me how he was doing his job, but I had access to a studio full of equipment. It was a dream for a beginner photographer. I was no longer limited by the equipment, as many people are, but I was able to experiment fully with everything. So that took 3 years working for this photographer and finishing my studies. Out of 30 students starting the program that year, only 2 finished. I was one of the two.

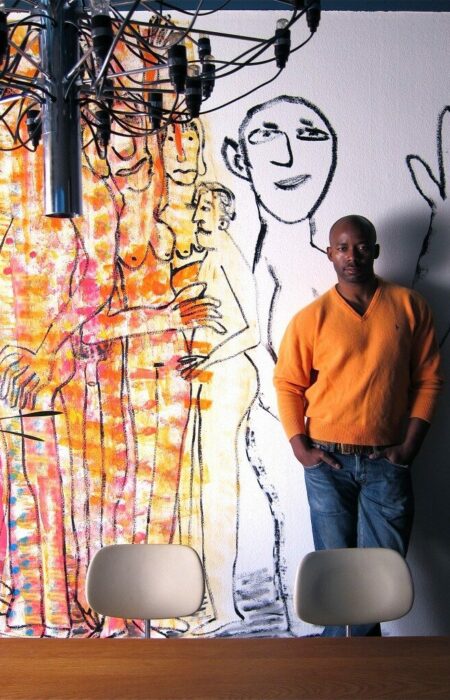

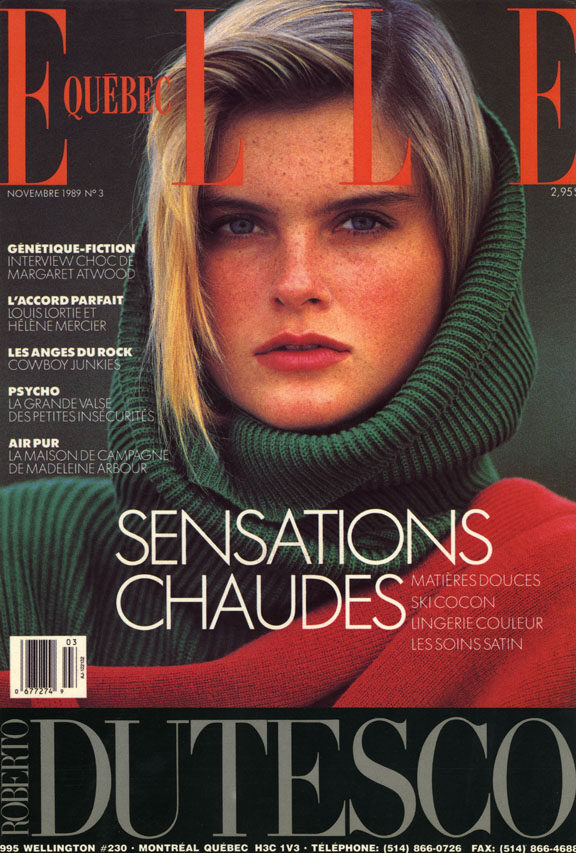

Things took off pretty quickly from there, and within a few short years you became a highly sought-after fashion photographer with photos in Elle, Flare, Allure, Vogue, Rolling Stone and other publications, by then opening your own photo studio in Manhattan. This must have been a heady time.

Being involved in the fashion world, I started working for a few magazines. Elle magazine had just opened in Canada, and I almost got the first cover of the magazine. I did not get that first cover — I believe it was Linda Evangelista with Patrick Demarchelier that got it — so instead I got the second cover. So once I got the second cover of Elle magazine, my name went everywhere.

Elle magazine cover by Roberto Dutesco

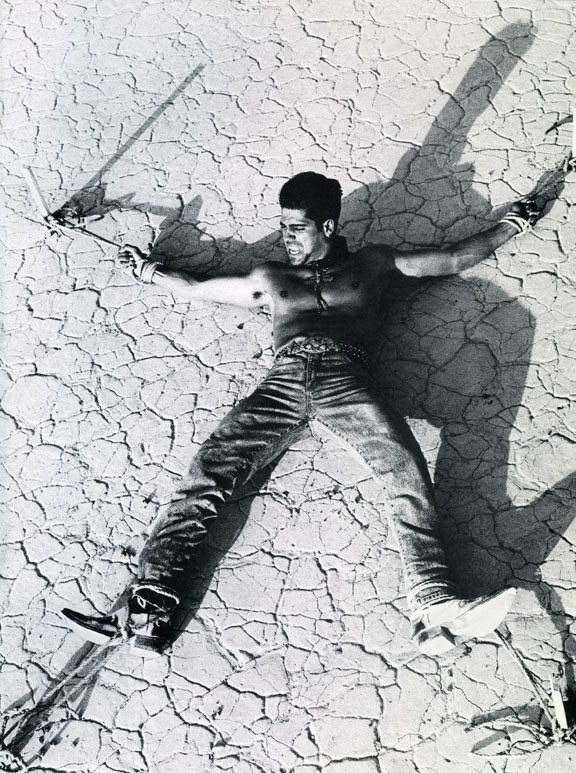

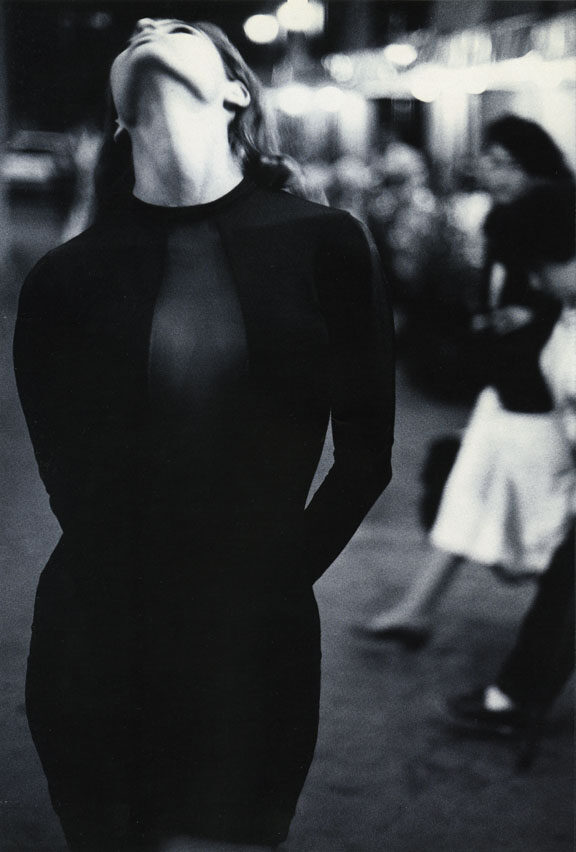

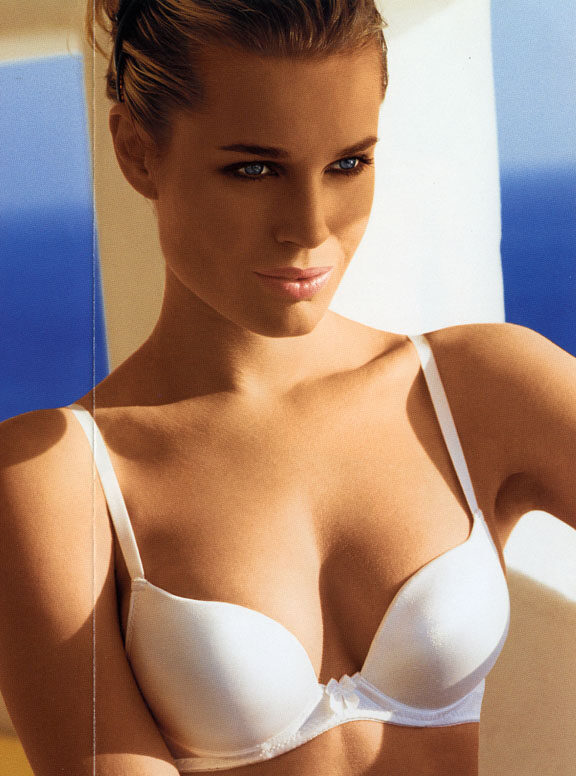

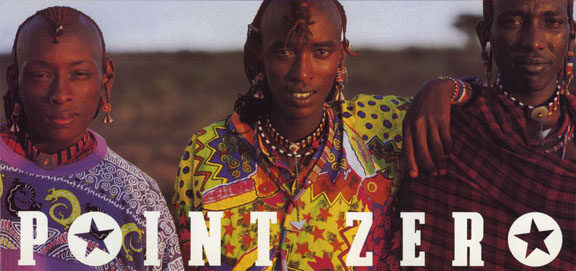

I also did a fabulous brochure for an amazing store, VERI, in Montreal that was carrying the main fashion brands — Armani, Versace, and Ferré. That was probably ’88 or ’89. So because of those two campaigns, all of a sudden everybody started to know my name, and I started to do a lot of fashion campaigns. And I specialized in jeans campaigns. My photographs were very hot, they were very racy, they were very spicy. I did a fashion campaign for a company called Request Jeans, and their ads were publicized in Details magazine in the U.S. It went across the U.S. at the same time as Kate Moss’ campaign with Calvin Klein Jeans. It was the time of the supermodels. It was one of those campaigns that would become memorable and would always be there. That campaign inspired many, many people throughout many years. Because my name became known, I started to shoot more and more campaigns. I started to do a lot of sportswear for Suzy Shier, lingerie for La Senza (now part of Victoria Secret), and racy, spicy ads for Lee Jeans, Hollywood Jeans, and Buffalo Jeans. The Point Zero campaign was also a decisive moment. I stayed with those campaigns and editorials for 10 years or so.

Request Jeans ad photograph by Roberto Dutesco

Photograph for Santana Jeans by Roberto Dutesco

Lingerie photograph for La Senza by Roberto Dutesco

In 1994, you made your first trip to Sable Island off the coast of Nova Scotia and have returned many times to photograph the wild horses there. What first drew you to Sable Island, and did you have any idea the impact these images would have?

Very much just by sheer luck, one night I was Montreal and was just watching television — this was in ’91 — and I came to a channel with grainy footage of this place that had some wild horses and incredible scenery. And I had no idea where the place was. Of course, finding out it was a Sable Island, a Canadian island — with 400 horses, 500 shipwrecks, no people living on the island — I made myself a note. This was when I was traveling extensively for my fashion work, and I put that note in a very safe place — and I lost it for about a year and a half! And then, as things come back, I was looking for something, and this note came to me. And I said ‘oh, my god, Sable Island, and I have never gone there, I have never done anything about it.’ So I started to inquire about what I can do about Sable Island — and I just wanted to do something other than my fashion work, which is transitory and has its own moment, and then it’s gone. I thought how wonderful it would be to be on the opposite side of fashion, of jeans, of lingerie — to be in a place where nobody knows your name, and you’re virtually the only person around.

Did I have an idea what impact they would have? Absolutely not, no. But I know the attraction was there, and the curiosity I have always been very proud of made me inquire more and more about it. And the more I got resistance from visiting Sable Island — as there are no visitors to Sable Island — the more I was intrigued by it. I had to explain to different levels of government, and there were many permissions I had to get to go to Sable Island. When people would say, “What is it that you do?”, I would say, “I am a photographer.” They would say, “Where can we see your photographs? Can we see them somewhere?” At the time, the world wide web did not exist, and I would simply say to the people in Ottawa, “Do you have any fashion billboards outside?” And they would say yes and would name the brands that were on those billboards, and I would say, “Well, those are my photographs.” So it was very easy for me to explain to them that I’m a photographer, and it was very easy for them to understand I’m not going to Sable Island just because I have nothing better to do. I was a very busy photographer, shooting perhaps 150 days a year, sometimes more. And they said, “Wow, so you really want to do this? What are you going to do with it?” My answer was always the same and still is: to raise awareness about Sable Island. I knew instinctively it was important for me to go and do this. That was the beginning of my Sable Island quest, of the voyage that is now 15 or 16 years in the making.

“Fury” – Wild Horses of Sable Island series by Roberto Dutesco

Wild Horses of Sable Island show by Roberto Dutesco

The connection and rapport you developed with these horses is profound. How did you gain their trust and affection?

What I can tell you is this. We tend to differentiate, we tend to put labels on things, we live in the world of words. But this world does not necessarily allow us to understand, just because we know the word, what the actual subject matter is. If I’m photographing faces or oceans or trees or leaves or flowers or horses, my perspective towards that moment is that as I am observing, the subject observes me. As I have photographed models throughout my many years, I have learned that the more you observe the person and the more you try to understand not just their physical beauty but really to understand who they are and to always go beyond that apparent beauty, then the models have always responded to me in ways in which they may not have responded to other photographers. And I have done it instinctively — I have not done it with the idea that I would gain something more. I was not looking for something more. I was looking for what is. And in nature, I have learned that if you respect whatever you are observing, you have to respect with gratitude, you have to respect with knowledge, you have to respect with understanding.

So after many years of travels and models, when I ended up seeing these horses, then the actual connection was not that difficult to make. The philosophy of my life and the philosophy behind my photographs was unchanged. I did not do anything different there. What I tried, if I have tried anything, is to forget what I have learned. I’ve tried to make myself as small as possible, as insignificant as possible, as invisible as possible. I wanted to be non-intrusive. I was invited to be in their home, into their land. Sable Island, in regards to the horses, is their own universe — basically a world unto itself. Those horses have never been taken from the island, they have never seen anything else but that island surrounded by water. As far as they’re concerned, they are the kings of a place in the middle of the universe, just like we consider ourselves to be in this larger universe. So that was my philosophy behind the Sable project, behind photographing it, behind talking about it, and behind taking it to the next level, however that level presented itself to be. I think that whatever I have done in regards to Sable Island, I’ve done with the acceptance of Sable Island somehow and almost being guided. I’ve always said that Sable Island has a mind of its own, and it works with me, but it works without me as well. It’s quite incredible to me all these years later how many people have actually been touched by these horses, and that happens every single day.

Chasing Wild Horses – Clip 2 of 4 from Roberto Dutesco on Vimeo.

Was your Wild Horses of Sable Island series the beginning of your work in film? And where do you see your film work going?

Prior to becoming a photographer, I always wanted to become a filmmaker. Photography in many ways was an interruption prior to film, and I still dream of becoming a filmmaker. Instead of just waiting to become one, I’ve always shot a lot of film. Whenever I have traveled, I have always had a digital camera or recorder of some sort and my many cameras. So when I went to Sable Island, to me it was only natural that I was going to continue that trend. After thousands and thousands of hours, I’ve always made a joke if I was traveling around the world that it’s “Dutesco reporting from…” And, believe me, as I’m telling you this — it’s kind of funny to me, I haven’t said this in a long time — I must have said that many times in hundreds of locations around the world. That was prior to the Travel Channel!

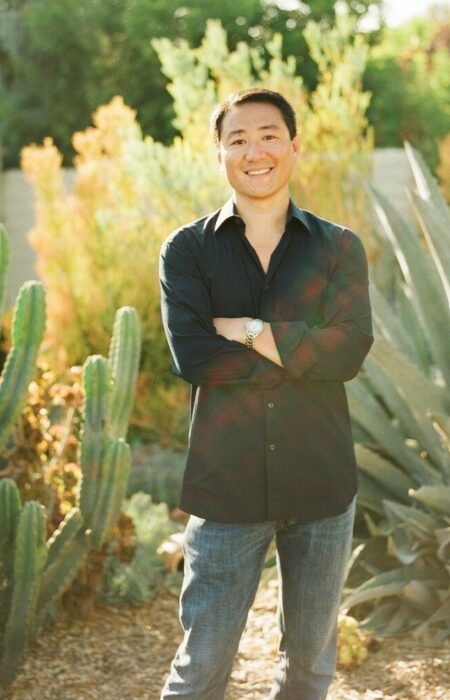

Photograph of “Robert Dutesco reporting from…”

So I ended up on Sable Island with an Arriflex camera, an older camera I had only used twice before, and I had to learn to use it while on Sable Island. It works with magazine backs in which you load 100, 200, or 400 feet of film, and basically it runs for about 4-12 minutes. I travel alone with all my cameras, with all my digital recorders, with all my medium formats and large formats, 35mm — I mean, it’s a lot of stuff. And to take off on this 16mm, it was a huge challenge. As my hands were in the bag loading or unloading film, many things were happening before my eyes. And, of course, if you are loading film, there is not anything you can do about it — you have to finish what you are doing, otherwise you will ruin a whole role of film. So I learned at that moment that film versus a digital recorder is a lot more precious, a lot more beautiful — and it made me pay more attention to my subjects. Even now today, I’m shooting film and not digital. So I knew photography might be sufficient, but eventually a film about Sable Island has to exist.

I approached different film companies with the idea that perhaps they can take the project further, and they can do a film about my journey. Luckily enough, 13 years later, a company called Arcadia from Halifax (strangely enough, just across from Sable Island!), decided that the 16mm film was interesting, and they took it and presented it to Bravo television in Canada. Bravo thought the story of Sable Island was fantastic, but also the story of the photographer was very interesting. So the film Chasing Wild Horses basically evolved at that level of connectivity between where I have started and where I have ended up.

So that is the beginning of film. But in the meantime, I have done many other things, many other subjects. For me, the ultimate project I have done is called Times Squared, which is a visual journey through about 40 countries around the world, which was a comprehension of what I have seen compressed into about 20 minutes. I have a feeling that the Sable Island film, when completed at the end of 2009, will be an ultimate project as well.

In 1998 you traveled to over 40 countries, even meeting the Dalai Lama. What inspired this “One World” photographic journey, and did you have a sense of a larger mission?

The One World project started at different stages. At one point, just like every other explorer, I just wanted to see if the world is round. So I bought myself a round-trip ticket for a trip around the world, and not with a precise destination but with some precision points in terms of where I was going to stop and why. I have always been fascinated by ancient cultures, and I have always been fascinated by rocks. My fascination with rocks has been there since I was a child and was playing on the river bed in the back of the house where my grandparents lived. In my place in Montreal where I live, also I have rocks from all over the world, from the many countries I have visited. I have a ton of rocks everywhere. Here in the Wild Horses of Sable Island Gallery, those rocks are completely rounded and come from the old glacier that pushed all those rocks thousands of miles, finally forming Manhattan and Long Island. So the actual working title of that film, even though it ended up being called Times Squared, was Rocks and Things.

“Kilimanjaro” photograph for Point Zero campaign by Roberto Dutesco

I believe in many things, and this exploration of this larger world that I live in has always been on my mind. So the 3 months I have taken in this travel, perhaps it was the most important journey of my life. I flew business class so I could sleep on the plane, not knowing where I would sleep when I was on the ground. I slept in palaces, and I slept in forests. And that experience of being nomadic allowed me to experience nature and earth at a different level. While I was traveling, I photographed my journey, and the book is going to be titled Rocks and Things. And then, of course, at the same time I have filmed it, and that’s how Times Squared came about.

“The Taj” photograph by Roberto Dutesco

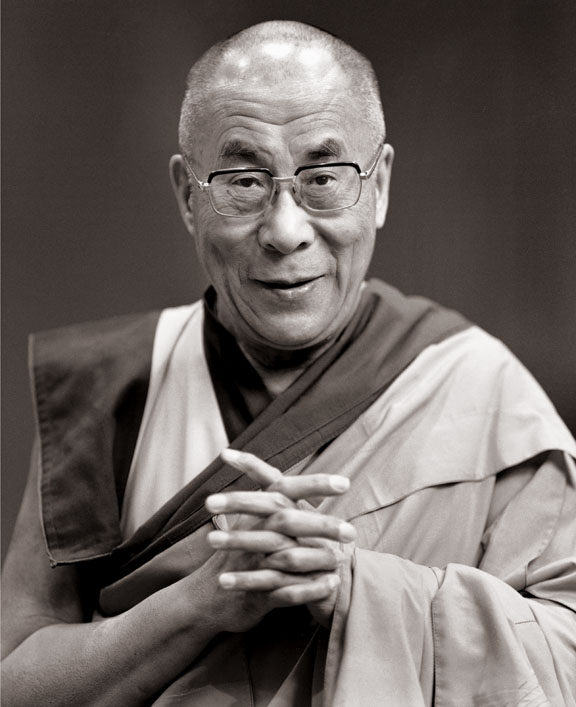

In regards to the Dalai Lama, I had never met him before. The idea came to mind that he inspires people with his vision of peace and a better world. It was not a political message, it had nothing to do with politics. I was fascinated with his philosophy and the fact that he was awarded the Nobel Prize for Peace. And that philosophy of peace inspired me to travel to the northern part of India to Dharamsala, with the anticipation that I was going to be granted an actual sitting for a portrait. That was supposed to happen during the Tibetan New Year, but instead of him attending, the whole ceremony went on without him there. But strangely enough, immediately after — and maybe because of my insistence — I was granted a photo opportunity at a different place with his Holiness and have photographed him several times since.

Portrait of the Dalai Lama by Roberto Dutesco

I was offered a chance to exhibit in downtown Montreal over 4 city blocks an idea, and the idea was about peace. So as I had just come back from this journey to 40 countries, I just presented the idea that we live in a single world, without any borders — hence, One World. As I was traveling, I was very fascinated by the ocean and the currents, a fascination that started on Sable Island. We tend to break this world apart with borders. However, when you’re traveling, you don’t see these borders unless you are looking over a barbed fence. And even if you’re looking over a barbed fence, that barbed fence stops at the water point. So the currents have no borders, and the water travels freely throughout the world.

Back in Montreal, I presented this idea, and the larger mission of One World was exhibited over 4 city blocks for the whole summer of 2004. So the larger mission is to put the world together, to expose the world to its beauty. I’m very much about beauty, and I’m very much about peace in general. My notion is that if you show positive movements, positive outcomes, positive photographs filled with as much positive energy as they possibly can, perhaps that would be transmitted further into the world. And then perhaps those people looking at those images will be touched, and they will take that energy further. So that is really the ultimate mission here, if there is any.

Here Is Now public art exhibit in Montreal by Roberto Dutesco

You’ve taken some stunning photographs of flowers for your Ethereal Reflections series that are available as a book and that were featured in a series of Lord & Taylor window displays earlier this year. Tell me about your creative vision with these images and a bit about your technique.

I have always gone back to that first flower photograph that I did on Mount Royal. And throughout my many years as a fashion photographer, I have always attempted to take time and photograph flowers. I believe it was sometime in the ’90s, I was given an opportunity to photograph some flowers for Sony Corporation for their Madison Avenue windows. So I had 6 windows to be filled with flowers during wintertime. Of course, winter in New York is very grey and is not necessarily the most pretty place to be. So I thought, ‘wow, flowers…what can I actually do with them?’ So I took the time to think ‘how do flowers feel? do they feel?’ And what is it about all these colors, and how can I actually show them? How do they respond?

So I was photographing some tulips in a way that I have never photographed before, and as I brought my camera very close to the actual tulips, I would see the movement in the opening of the petals! That was a very special moment for me, and it came by chance. In that excitement, I was photographing with this camera which is not complicated, but it was a Hasselblad. On Hasselblad when you do macro photography, if you’re shooting at a different f-stop rather than just being wide open, you have to close down. It’s a very simple procedure, but in my excitement of this happening, I wanted to photograph the flower as it was opening up. So I forgot to close down the camera, and the image became overexposed. So through an accident, I have achieved this surreal image that I would have never done otherwise if I had taken the image in a normal, conventional way. So that took me further into the exploration of flowers, experimenting with movement, with different lighting techniques, and with light being a vibration itself.

“Bliss” photograph by Roberto Dutesco

“Young” photograph by Roberto Dutesco

After the first show of flowers at Sony Corporation during wintertime, I had one other show with flowers that was mixed together with poetry. I exhibited them at my gallery at 13 Crosby in SoHo, New York City, where the Sable Horses show is, and I called it Poetry on a Wire. I called it that because physically the whole exhibit was shown that way — there were some wires run across the wall that remind me of hanging clothing, and I hung some photographs of flowers and poetry in between. My idea was to exhibit the flowers and the poetry together, and this came to a realization this year, in fact, again in a public display.

I believe that the public displays of art are the most important forms in which artists can actually bring our art to the public. Not so much in galleries, but bring them onto the streets. So Lord & Taylor this year gave me their windows for one month in a show called Ethereal Reflections. And it gave me a chance in their 26 windows along 5th Ave. to show 26 poems and 26 flowers. Some of the poems were very romantic, some of them were very daring, and some of them very naive. I do not pretend to be a great writer, and I’m certainly no Shakespeare –I just like to write.

One of 26 windows in Ethereal Reflections series by Roberto Dutesco at Lord & Taylor

As a department store, Lord & Taylor is just that — it’s for everyone, for every level of society to go in. And many art galleries become places where a lot of people are intimidated to go. I remember on my first visit to New York, I was intimidated to walk into the galleries — perhaps for the wrong reasons — there was so much knowledge and so much gravity and all these people in white shirts and black ties and black suits behind desks looking at you, almost questioning what you are doing there or what you want from them. So art for me became something that I was passionate about and curious about, but I felt I was somehow intruding into a world. And whether that was true or not, it doesn’t really matter — it’s how I felt. And I can tell you, many people feel it’s a big deal walking into a gallery. So public art is something I’ve always believed in. Lord & Taylor gave me this opportunity along with my book Ethereal Reflections, and I thought how wonderful to actually put this book together and just give it away! So I published 200 books, and I gave them away one night at Lord & Taylor.

I believe there is a larger energy out there that guides artists, and I feel that if we are at peace, we are allowed to connect ourselves with that larger energy. Anybody can connect to that. And I believe that whatever artistry we feel belongs to us is basically just being transmitted through us. I think that artists might have a larger connection to it, and I think that larger connection may get developed as you continue your artistry.

I’ve been at it pretty much for most of my life, and very seriously since I opened up my first studio in 1987. But I still consider myself to be at the beginning, and all the rules and all the things that I have learned in school have been forgotten. All that technique is no longer there. I’m no longer interested in sharp images or what type of ASA or what type of camera I’m going to use or what type of lens. All of those things become just tools, wires of connectivity into that larger energy that exists out there. And those decisions are no longer rational, they just simply are.

“Poppies Melting Away” photograph by Roberto Dutesco

Your poetry is featured prominently in this Ethereal Reflections series, as well as in your other work. When did you first start writing poetry, and do you now see it as key component in telling a larger story?

Poetry is something I have always written, and I started writing when I was very young. But I was not very good at literature, and throughout my early years I was not encouraged by my teachers. I find that teachers, if nothing else, should not discourage someone. So I was not really encouraged to write but from an emotional perspective have always been attached to it. So I started writing, and I have always kept throughout my many years a collection of my thoughts and my philosophy. I started them when I first moved to Ottawa from Romania with my family — I did not know anyone there — and, of course, my desire to express myself has always been a necessity. So since I could not communicate with anyone else in English, I thought it would be a good idea to communicate with myself in my own language of Romanian. Much of my writing began as notes about the actual journey itself.

So my first steps into writing started at that level of notes about my new experience moving to Canada. And throughout the many years, those notes have always been very important to me. As we travel, the actual news, the actual information, the actual vision transforms itself. And the actual stories, if you tell them over and over again, they always change again. We have vivid imaginations and vivid minds. So I started to write to keep that simple notion of the simplicity of the original intent, of why it is that I do what I do. What drives me, what pushes me. So fast forward, taking time from fashion and devoting more time to art and travel, I actually have a deeper desire to write. At one point, I decided to just write. And, as you have to be disciplined about that, I decided to write 100 poems. I didn’t know how long that was going to take, but I decided to wake up in the morning, go into the office and from 6:00 to 9:00, just simply write. So I was very specific about it, and I did write for about 2 years. I ended up writing about 150 poems, and then I stopped. Now poetry comes to me every once in a while — it comes to me very early or very late at night. I do not correct much of it, nor do I actually go over it — so it almost feels like a dictation. I write it, and then I simply move on.

Looking at your range of photographs — people, horses, sand dunes, rocks and flowers — do you think about an overarching aesthetic across your work?

I do not really make a difference between them — they are just subjects that exist. And, of course, it is different if you photograph a flower or if you photograph a rock or a wild horse, the ocean or the clouds, strictly at the immediate level. But if you break them down, if you look into them, there is a larger energy that resides within. And that energy does not necessarily show when you are on that photograph visually. However, even though it does not show, I believe it resides in that photograph somehow in some strange, wonderful level. There is a deeper connectivity. The old North American Indians — and perhaps many cultures throughout the world, the gypsies — they do not want their picture to be taken. The idea is that when you take a photograph of them, you take a bit of their energy that resides within. And whether that is true or false, I can tell you that if I go back to some of my photographs, that energy certainly resides in those photographs. People looking at those photographs feel something, and not always with the same photograph.

“Shadow – Dumont Dunes, California” photograph by Roberto Dutesco

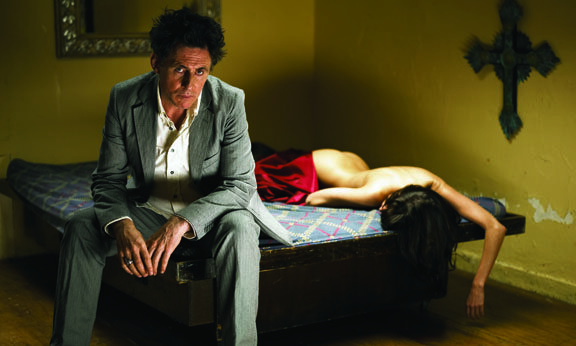

Photograph of Gabriel Byrne for CP Company by Roberto Dutesco

“Claudine” photograph from The Human Landscape exhibit by Roberto Dutesco

You dedicated your book Ethereal Reflections to the young children of the world, and included a note to parents to encourage our children to be curious and explore and attempt to live their lives “divinely aware.” This phrase, divinely aware, seems to get at the heart of all your images and your work in film and poetry. What do you hope your contribution to the world is through your work?

Wow, my contribution to the world? It’s very difficult… I can reduce all this perhaps in a simpler way. The contribution to the world is what is going to be — the world will decide that, whether what I’ve done or what I’m doing is important or not. Whether they are attached to it or touched by it in a certain way or another, so that is not something I can really answer.

However, my immediate contribution to the world is through my daughter. She is 1 year old, and her name is Maya. As she’s growing up right now without any words but a lot of intent and a lot of curiosity, she explores this new world with new eyes. And I think that those new eyes are pretty much the eyes of the eternal. What she does is very important — she is pointing at things. I cannot really teach her everything, but I try to encourage her to look at those things, to look at the flowers, to look at the paintings we have on the wall, to encourage her — from a visual perspective at least — to be very curious about her immediate surroundings. And to be curious at a certain level to know there’s a larger world out there. I was fortunate enough not to grow up in a city surrounded by concrete blocks but to grow up at my grandparents place surrounded by forests and nature. And basically nature has a way of teaching you that everything is transitory and everything changes. And if you know that that is the case, perhaps when you are face-to-face with something, it’s an important moment. Maybe you should actually respect that moment with different eyes. So if you do that, perhaps you may be able to connect with what’s in front of you at a deeper level, perhaps in a mystical way. So to me, that is the contribution to the larger world, what I’m trying to show my daughter. It’s the only thing that we can do. And whether that means she is divinely aware or not, my intuition tells me that all kids when they are born are divinely aware.

“Havana” photograph by Roberto Dutesco

What are some of your favorite things in the world, whether they impact your work directly or just make you happy?

It’s an interesting question. Luckily, at my grandparents’ place, apart from the amazing forest, the hills, and the river behind the house, my grandparents had the most incredible library. It was that library that made me be very curious about the world. The first book I ever read was Travels Across the Pacific by Thor Heyerdahl, the fantastic explorer that took his raft across the Pacific and proved that the ocean can be crossed in a bamboo raft. The second book was Easter Island, which lies isolated in the Pacific, pretty much the same way that Sable Island is. So the idea of exploration, it is perhaps one of my favorite things in the world. The idea of discovery. And whether that comes through food, through voyages in the many countries, through music, through the great philosophers of the world, or through an amazing story, one of my favorite things is to learn. And, of course, that extends itself in pretty much every other area of my life.

Photograph for CP Company by Roberto Dutesco

I am pretty much black and white: I know what I love, and I know what I don’t. What I love, I love a lot. And what I don’t, I do not get that attached to it, or I do not really get that much disappointed by it. What it means is that I really do not understand it. So I would like to think that I spend more time with the things that I like and try to accept those things that I don’t. At some level, I have to agree that not everything is rosy. And we live in a world with incredible conflicts, rage across the borders or the borders of the mind. The most important thing is to believe that everybody, at the end of the day — even warriors — they want to go home. They want to go home to have a beautiful life, they want to go home to be with their families and with their friends, and perhaps die in a good sleep. So my feeling is, there is a larger desire that exists within every single person, and that desire is for peace. And my favorite thing is to believe that it is possible.

Roberto Dutesco

All photographs © 2009 by Roberto Dutesco

The Wild Horses of Sable Island Gallery is located at 13 Crosby Street in SoHo, New York City.

Share the love, post a comment!