As the first blind person to summit Mt. Everest, Erik Weihenmayer is already an inspiration. But somewhere in the process of losing his sight at age thirteen and then going on to climb the Seven Summits, Erik internalized an understanding of humanity that has now given his life even higher purpose. In addition to being an author, a highly sought-after speaker, and an award-winning athlete, Erik is an innovator who challenges how we perceive adversity. He helped a group of blind Tibetan kids climb to Mt. Everest’s advanced base camp, changing their own view of themselves and whole cultural perceptions. A highly creative thinker and visionary, Erik proves it’s not our eyes we see with.

Erik Weihenmayer on the cover of TIME magazine

Find an expanded interview with Erik Weihenmayer in my new book Field Trip:Volume One, available on Amazon here! Or read more about my new book here.

You’re someone who has been incredibly creative and tenacious in pursuit of your dreams and goals, which I imagine was in the face of well-intentioned advice from others. Can you share your own advice about evaluating strengths vs. passions in choosing a path forward?

Well, I think I will start by saying that I’m not a soundbite guy, because there’s no magic little thing that’s going to sound great in an answer here. For me, the excitement of life is that sort of journey of figuring out what your strengths are and what your passions are. There’s no way to separate it. You know, I’m a climber, and I fell into climbing. I only turned to climbing because I couldn’t play basketball anymore. And because I couldn’t do that and I wanted to be an athlete — my brothers were both athletes and my dad was an athlete — I wanted to figure out how to do it too. So I just stumbled upon rock climbing. I had no idea whether I’d be good at it or whether I’d like it, and so it was all about kind of reaching out and trying things and figuring it out. And so I would say my advice to people to find their strengths and their passions in life is to understand that the struggle of reaching out and trying things and stretching yourself really is an uncertainty about what the course of your life is going to be about. That begins to define your life and begins to help you understand what your course is. So it’s the struggles, it’s the failures where sometimes your strengths and your passions are ignited.

It’s awfully difficult to assess what your strengths and weaknesses are. You know, there are a lot of books out now that sort of talk about playing to your strengths, and don’t worry about your weaknesses. You know, kind of let go of your weaknesses, because you can exponentially grow your strengths, and with your weaknesses you might be able to get only incremental improvement and you might as well not waste your time. And that’s an ok argument. But any argument taken to the nth degree is almost dangerous. You can take it too far. So I think that you don’t really know what your strengths are until you’ve struggled and failed and failed again, and really gone through that process of exploration and pioneering to kind of figure out what they are. And through that experience, oftentimes those strengths and your clarity and your vision are formed. So you have to go through the pain to begin to clarify your life. It’s impossible not to.

It’s easy to write things off and say, ‘Ah, I’m not good at that.’ But you don’t really know — that’s the tricky part of that theory. And I think those theories of playing to your strengths — you know, just sort of inputting your strengths like a computer and then out pops your destiny in life — I think that’s a mistake. I think what you do is if you have a love of something or an interest in something that you’ve developed, or you think about the impact you want to make or the legacy you want to have in life, you start with that and then figure out how to get there. And you develop the strengths needed to get there. Some of them you have, some of them you have to struggle and develop, and then others, if you’re never going to have them, you just surround yourself with great people who will help you become more complete.

Watch the heart-stopping progress of Erik and his team as they work toward summiting Mt. Everest.

Were you always confident that you would achieve your goals?

When you’re young and you have done nothing, you have sort of this burning passion to do something, to make your mark in the world. And so I definitely had that passion, that drive. And sometimes that would get me in trouble. I remember training for Mt. McKinley. I lived in Arizona, which wasn’t the best place to train for mountains at the time, but my friend said, ‘So how are we going to start training for this? How about we do long runs through the desert?’ And I said, ‘Yeah, I can do that, no problem.’ And I would run with my guide dog, but there were parts of the trail that were really narrow. And I think it was our first training session that I tripped and landed on a cactus and had to go to the emergency room. It was my first training session for my first big mountain. So sometimes that drive kind of gets you in trouble, but it also can motivate you.

And when did you determine this goal of climbing the Seven Summits?

Well, I lived in Arizona at the time. I was a teacher and I loved teaching — I taught fifth grade math and English, and I could have taught forever — and I told a friend of mine who was a teacher at the school that I’d like to climb, just basically rock climbing. And we’d go out climbing on the weekends, and we were climbing some rock face that was kind of hard. I got to the top, and he said, ‘Hey, we should try something bigger.’ And I said, ‘What do you think that should be?’ And he said, ‘How about Mt. McKinley?’ And that’s a leap going from rock climbing in the desert in Arizona to climbing a 20,000 foot, huge, glaciated peak in Alaska. But I got excited.

My friend had attention deficit disorder, so he was a guy who could take a big leap in life, but I couldn’t do that without being prompted. But once the idea was out there in space, I could then sort of figure out how to get from point A to point B, I could develop the plan how to do it. I have a bit of a linear mind, so I sort of developed our training plan, and we went out and trained on mountains all over the country — and failed on all of them! We never summited anything. But in that failure, you know, getting turned back on mountains in the Rockies, in storms, we kind of felt we had gone through a lot, that we’d tested ourselves, that we were ready. And I didn’t know if we were going to summit Mt. McKinley or not. You never really know if you’re going to summit a mountain or not. I mean, of course, you believe you are because that’s the way you have to proceed — you have to see yourself completing it — but you still never know. You just never know what’s going to happen. But you go forward totally prepared to succeed. So we were ready for McKinley, and we flew onto the glacier and faced a lot of storms, but we summited on our 19th day on the mountain. It turned out it was Helen Keller’s birthday when we summited, so that was pretty cool. But getting there, I worked harder than I ever had in my life. There were days when I was so absolutely wasted and felt like I could not take another step, so it definitely was a great learning experience. Because whenever you do your first big thing in life, you realize how hard you have to work and what a mental struggle it is. So when I look back — this was sixteen years ago — I still think that was my hardest peak because it was such a game-changer for me.

It’s funny, because there were so many times throughout that climb where I thought, ‘I am not cut out for this. This is miserable, what am I doing here?’ And I finished the climb and I slept for like three weeks when I got home — I just slept, I was so wasted, I’d lost a ton of weight. But it’s funny, because three weeks later, you wake up and you’ve forgotten all the terrible stuff and all the suffering. And all you remember was the great camaraderie between your friends, and standing on top, and going beyond your expectations. All the good stuff comes out, and all the bad stuff just sort of drifts away. That happens every single time you go to a mountain.

I knew Kilimanjaro wasn’t as hard — it’s one of the Seven Summits — so I was kind of on the Seven Summits course to climb the tallest peak on every continent. And I didn’t even know if I could do it, but I thought I’m gonna set myself on a trajectory and I’m gonna try and see if I can do this. And I thought, ‘Hey, maybe I’ll get five out of seven!’ But I was keeping my mind open to the experience and trying to grow and figure out how I could do this stuff and wrap my head around this stuff. And Kilimanjaro was not as hard as McKinley, but it turned out to be pretty hard, and I just kind of kept going. And it was only like a month before I was planning my next trip.

Erik Weihenmayer on Mt. McKinley, photo by Jamie Bloomquist

Erik Weihenmayer on summit of Mt. Kilimanjaro

Erik Weihenmayer on the summit of Mt. Cook, New Zealand, photo by Eric Alexander

You’ve written books and have done speaking engagements and so many other things now. At what point did you begin to internalize and share these larger lessons that have led to this part of your career?

I had had a lot of personal successes on big mountains before Everest, but I have to say, I think Everest was the paradigm shifter in my life. When I thought about climbing Mt. Everest, when I was training, I thought about all the massive hurdles and was realistic about all of them. When you go to a mountain and you can see it, you look up at that mountain, and you’re just so intimidated by this massive peak. And not only the physical nature of it but the folklore and the legend behind it, and Mt. Everest obviously has all that. You know, hundreds of people dying and struggling trying to get to the summit. So when I would think about climbing Mt. Everest, it almost defied my imagination to see myself standing on top. It really was quite a struggle to keep myself from going, ‘What the heck am I doing?’ It was a real mind game. So to go through the experience and actually reach the summit, it might have changed other people’s ideas of what was possible — well, first of all, it changed mine! So that was another big game-changer for me, because I now realized what it took to do something that seemed pretty near impossible.

So after that I got home, and life was totally crazy. There was paparazzi at my house, and Oprah calling, and I was on the Tonight Show, and all that kind of craziness. So the external life changed, but also I started to think, ‘OK, maybe I’ve gone through enough that I might have something to teach other people. Maybe I have some things that could help people.’ Kids in particular, and not necessarily blind kids, but kids who have challenges and who have their own struggles. And that’s pretty much everyone, almost. And that’s when I wrote my first book, which was more of just a memoir, just a book where I wanted to share with people. Because I think the best kind of writing is when you take people on a journey and you say to them, ‘Hey, look, I don’t have all the answers, but let’s go through this experience together. I’ll take you on this journey, and we’ll learn together.’ And so a kid sitting in English class who isn’t blind reads that story and finds a lot of common ground and says, ‘Holy cow, I’m not blind, but, man, I relate to this guy’s experience! I struggle in a different way.’ So that was really my goal for that book: not necessarily to teach people anything, but to kind of find that common experience.

It wasn’t until my second book, The Adversity Advantage, that it became more of a how-to book. I teamed up with this co-writer named Paul Stoltz who had studied resiliency around the world, and we wrote this book together about how to confront and harness adversity. He kind of came at it from the science side, and I came at it from the experience side.

Erik Weihenmayer and his team on the summit of Mt. Everest, photo by Luis Benitez

Erik Weihenmayer on Times Square billboard for Foundation for a Better Life

How do you assess risk?

First, I would say I’m not a blind Evil Knievel, you know, getting shot across the Grand Canyon. I’m not looking for a way to defy death. For me, the exciting part isn’t about the risk. The risk is not the end-all. But it is something you have to assess and work your way through in order to have great rewards in life, to see great things and experience great things and have success. So risk is like one of those necessary evils that you have to figure out how to master — or work with it, but never master. And it’s a struggle to do that. Climbers especially assess risk all the time, and a lot of the great climbers are dead. They say there are a lot of old climbers and bold climbers, but there aren’t old and bold climbers. So you’ve got to be careful. I’m not a big risk taker, but in a sense, you have to lay it out there. You have to know when to lay it out there on a mountain, because you’re never going to summit anything unless you’re willing to lay it out there. But, at the same time, you do it in a very, very careful and strategic way. And you don’t do it all the time. It’s a science and an art to know when to lay it out there. And it’s something you learn your whole life, and you make a lot of mistakes along the way. It’s a real balancing act.

You know, I’ve turned back on probably 50% of the mountains I’ve been on. And there have been mountains where I’ve said, ‘Come on, we’re a half an hour from the summit! I’ve got the summit fever!’ And my friends turn us back, and thank god they did, because things might have gone really bad, you know? And then I’ve been on big peaks where you say, ‘We’re almost there, let’s keep going,’ and the lightning’s exploding all around you, and you squeak through and you high-five it in the parking lot. So it’s so tricky to figure it out. And a lot of times it’s easy to say, ‘Ah, the mountain beat us this time,’ — and when I say mountain, that could be anything. But when you look at a situation, it’s so easy to relinquish control and say, ‘Well, the weather and the conditions weren’t right.’ So the point is that the elements, the environment, it isn’t going to change for you — it is what it is. The only thing you can change is yourself. So I’ve always thought, ‘OK, the mountain is what it is, and I have to adapt my approach to make it work for the situation that I’m seeing, that I’m experiencing here.’ And it’s a very sort of pragmatic and sort of brutally honest way of approaching life. You don’t see life the way you wish it were, you’ve gotta see it the way it is. That for me is the first step in succeeding in any situation and then adapting my approach to that situation.

Erik Weihenmayer climbing Ama Dablam, photo by Didrik Johnck

Erik Weihenmayer in Arctic Team Challenge in Greenland

Erik Weihenmayer climbing ice fall in the Himalayas, photo by Rob Raker

I love your examples of what you call positive pessimism: “You may be blind, but you sure are slow!” or “It may be cold, but at least it’s windy!” So in this economy, I guess we’d say, “It may have been a near catastrophe, but at least it’s long and drawn out!” Is part of harnessing adversity about keeping a sense of humor about it?

Yeah, it definitely is. Positive pessimism is sort of a bit of a dark way of laughing at yourself and saying, ‘Hey, we may be facing a tough time right now, and it’s hard to see the light at the end of the tunnel, but we’ll get through this together.’ It’s sort of like asserting a bit of control over your course. And there are big overwhelming challenges right now that we’re facing, but if you can make a joke about it, it’s sort of like you’ve pulled it into your control a little bit more than before.

And I also think that, yeah, we’re in a challenging time right now, but when people are facing challenges, that’s the greatest time of growth. So this is the time to really be making ground, rather than just kind of digging in and holding ground and trying not to retreat. When adversity strikes, it’s a very pivotal moment where you can make really great progress in your life. So I guess I believe the opposite of sometimes what you’re taught — that in a crisis you just sort of hang on. I think in a situation like this, this is like an earthquake. The ground’s moving underneath you, so use that energy to propel yourself forward.

In the following video clip, Erik discusses one of his early inspirations and his philosophy about harnessing adversity.

Your climbing entails life-or-death choices, which may seem a world apart from the theme of art and design. Though for the creative people I’ve interviewed, I think it does feel like a life-or-death choice, and many have taken enormous leaps of faith to pursue what they love. Do you have a philosophy, especially after experiencing so many different cultures, about what our purpose is in life?

One is that life is unfair, that it’s really unfair. You know, you’re a baby born in Africa and you live a month and you’re eaten by termites. Or you’re born blind, or whatever. I mean, life is just not fair — and, in fact, it’s terribly unfair. But if you are given a chance to live a decent length of time, then what I’ve learned is that in a way it comes down to everyone being born with certain challenges or hurdles or barriers. And I think maybe a bit of the meaning comes from doing the absolute best you can, maybe even better than you think you can, with what you’re given. So taking what you’ve been given and just squeezing every bit of potential out of that and making an impact in the world and making a difference.

Erik Weihenmayer with one of the blind Tibetan kids he led to Mt. Everest’s advanced base camp, photo by Didrik Johnck

Erik Weihenmayer with teammate Jeff during Arctic Team Challenge

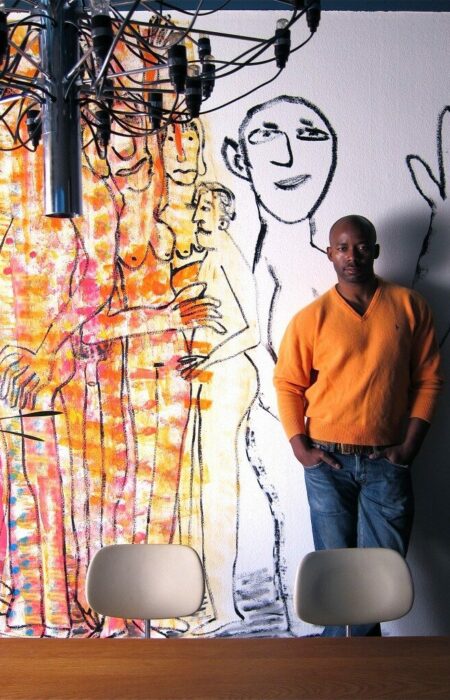

Erik Weihenmayer speaking at the Presidential Inaugural Conference

What is your involvement now with BrainPort, and what’s next on the horizon for you?

BrainPort is amazing technology. It’s basically a camera that I’m wearing on my head — nowadays it’s just a tiny camera mounted on a pair of sunglasses, it’s really come a long way. And it presents an image that tingles on my tongue. So it’s like 400 vibrating little dots, and when they light up in certain ways, they form lines and shapes and ultimately patterns and images. And so I can “see” certain things. So they’ve given me a BrainPort and asked me to test it out. So I can use it to read notecards. My son is adopted from Nepal, so he was learning English, and I could read the notecards faster than him. And playing games with my kids — I mean, that sounds like nothing, but to see what people are doing, to see your kids’ faces, and play little games with them and see what their hands are doing, it’s incredible.

I’ve been successful enough in life to have free time and to be able to make my own schedule and to be able to pursue things that I have no financial interest in. So BrainPort’s one of those — I’m just a happy volunteer. I like what they’re doing. I think it’s neat when you’re involved from the ground up with some of these things that twenty years from now that might totally make a person’s life different.

In the following video clip, Erik tests an earlier model of the BrainPort device that lets him see for the first time since he was thirteen years old.

On the horizon is lots of climbing. The ten year anniversary of our Everest climb is coming up in a year, and I’ve been organizing it. The guys I climbed with ten years ago, I haven’t lost touch with hardly any of them. We’re all still good friends, and we’ve done a lot of different climbs together. A lot of our lives were really transformed by Mt. Everest and that climb that we did. Like one guy went on to raft the entire Blue Nile from source to sea — 4,000 miles, and it had never been done before. And I think the team has gone on to climb Everest collectively eleven or twelve times since that first climb. So collectively the way the team has decided to give back is that we’re going to guide a team of injured military veterans to the summit of a peak called Lobuche, which is next to Mt. Everest. It’s 20,000 feet, so it’s 8,000 feet or so below Everest, but it’ll still be a good adventure.

What do you love about your work and your life?

I guess, what part of it don’t I like? I have a beautiful family. And I have a job where I work really hard, but I can make my own hours. And I get to travel and work with young folks on different adventures. I get to take people who sometimes might be pushed to the sidelines and teach them how to live in the mainstream of life, and that’s definitely fulfilling.

Erik Weihenmayer climbing in Thailand, photo by Charley Mace

Find out more about Erik’s speaking engagements, his work with teachers and students, his books and DVDs, or general information from his website.

Share the love, post a comment!