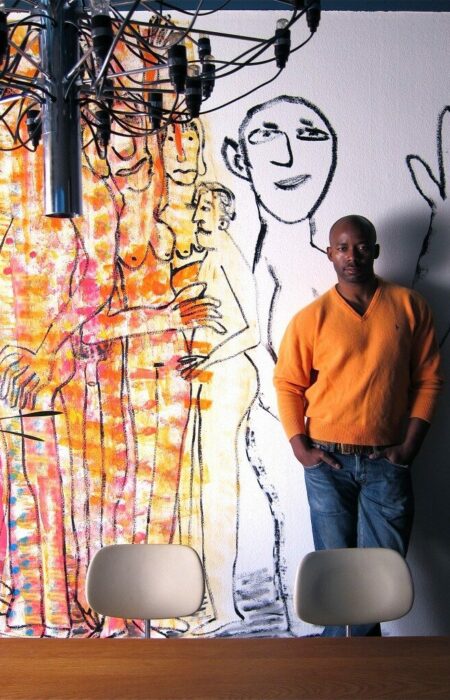

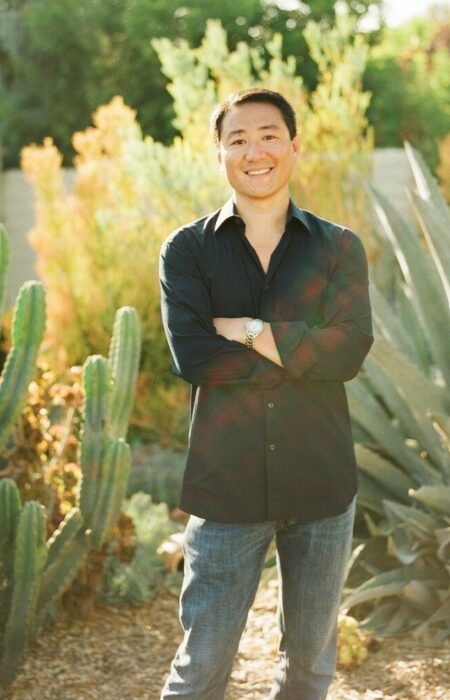

Artist David Trubridge brings a story teller’s sensibility to his designs in lighting, furniture and more. Driven by a deep commitment to the environment and to our cultural connections and nourishment, David explores forms in the natural world and expresses that beauty in ways that are spiritual and culturally meaningful. Whether his work is seen at retailers such as Design Within Reach or at an installation in a Milanese museum, David bridges the wisdom of indigenous cultures — such as in his adopted home in New Zealand — with a modern world in search of contemplative beauty.

Floral light by David Trubridge

Many, if not most, of your designs reference something in nature — ice crystals, coral, shells, and so forth. Can you tell me about your years growing up and what your early memories of nature were? And did you have an interest in art as a child?

My first ten years were lived in Scotland, and I went to school in the Central Highlands. I think that vital impressions are embedded in those early childhood years, and they remain to influence you for life. I used to love walking out of the valley and up to the wide open space of the heather moors and the rocky crags. Yes, I was very interested in art, much more so than making things. As a teenager, all I wanted to do in my spare time indoors was paint landscapes in the style of Turner and the Impressionists.

Kina light in chocolate by David Trubridge

To what level of detail do you sketch your ideas in advance versus jumping in and playing with the materials?

The design process follows a spiral where you go round and round repeatedly through different forms of exploration (sketching, materials, computer, etc.), each time (hopefully!) getting closer to the final result in the centre, and developing detail as you go. All parts are equally important, but I always begin with sketching, which is vital. You can never draw an expressive curve on the computer — the glyptic line that comes from deep within, from the physical sum of all your experiences. Drawing is so essential that you have to keep doing it to remain ‘in trim’, just as you might go to the gym.

Ruth 1 and Flip by David Trubridge

Koura light in black by David Trubridge

I know environmental concern is fundamental to everything you do, and you’ve said you think design that just stokes consumerism and is not culturally nourishing and environmentally sustainable is both irresponsible and irrelevant. How do you find that balance without stifling your own creative impulses?

My creative impulse is not naturally directed towards ephemeral fashionable consumer goods, just to produce stuff to sell. What drives me is an impulse to tell stories about the natural world and our relationship to it, and there is no reason why that impulse should be stifled by my environmental concerns. The problem comes in the vehicles for those stories — how can we make them truly sustainable without harmful impact on the planet?

Pebble bowls in bamboo by David Trubridge

Your forms are very light and skeletal-like in their structure. Do you design in this manner solely as a means of reducing the ecological impact of the forms or also for the interplay with air and light?

No, not “solely” — it is for a number of reasons, those two among them. I have always been fascinated by structure and by exploring its possibilities. Throughout my life as a designer and maker, my structures have progressively become lighter and lighter, to the point now where I wonder how I can just sell the idea without any physical form. This seems to parallel human development where, as our bodies age, physicality is replaced by conceptualising and spirituality.

Glide lounger by David Trubridge

Some of your best known work in lighting and furniture design uses bent wood, where the forms are the main focus. Now with your ITI Kitset Lampshades, I see color and the ability of the customer to arrange the pieces emerging strongly. Does this indicate a new direction for your work?

No, colour has played an important role for a long time. Look at our home and the furniture I was producing in the nineties. We have also been doing kitsets for some time, but this one is new in that it (fortuitously, as it happened!) allows the customer to play with it too. That is the fascination of structure. But what is newer is the use of plastic, which I am not entirely comfortable with yet. Instinctively I prefer to use wood because it’s a natural material. But for lighting, plastic brings a beautiful translucency impossible with wood. Also, which is the better material to use? Maybe plastic if it can be fully recycled? We are currently undergoing a full life cycle management (LCM) analysis of our business and products to assess things like this. But how does LCM take into account the nourishing aspect of wood — the connection it brings to nature?

ITI Sphere by David Trubridge

ITI Twister by David Trubridge

Your new installation in the Temporary Museum for New Design at Superstudio Piú in Milan with 3 hanging lights that cast a shadow on the floor were inspired by the ‘three baskets of knowledge’ in Maori mythology. How are people responding to these references, and do you feel a growing hunger for these spiritual stories?

It is too early to know what the response will be to the three baskets because we have not yet shown them. But I had a wonderful response to the Spiral Island installation I showed in Milan last year. One valued designer friend said that I am one of the few people with a story to tell, but sadly it gets drowned by all the other commercial noise. Maybe that is changing because, yes, I do see a growing hunger for stories — for more than the superficiality of clever gadgets or one-liner jokes.

Aluminum light installation by David Trubridge

Spiral Island installation by David Trubridge

You talk extensively on your website about your observations of good design using indigenous materials in the construction of homes around the world. What are some of the best examples of this good design, and tell me about your own commissioned work in architecture.

My favourite design is a bamboo hut built in Ethiopia which is like an upside down woven basket, covered in ’tiles’ made from the papery outer layer of the stalk. I am not suggesting for one moment that we go and live in these, but they are an ideal paradigm for all making: the materials grow locally to be replaced as fast as they are used. So this is true sustainable building which can go on like this forever. Unless we can achieve this with everything we use, we are surely doomed because we will run out of materials and energy.

My commissioned architecture didn’t really tackle these issues as I see them now. It was done in the nineties. I did try to make the houses as energy-efficient as possible using passive (and sometimes active) solar heating and thermal mass. I also tried to accommodate the very different evolving social needs of a family. The houses could be adapted to suit young families, teenagers and maybe later aging parents or tenants, so the owners do not need to rebuild. We have just finished building a holiday house I designed which uses (almost) all local untreated timber, wool insulation, bamboo, solar electric, compost toilet, rainwater, etc.

With such a mobile society and many yearning for other places in the world, to what extent does good design have to be indigenous? Can you find ways to take designs that are indigenous to one location and translate them to another?

I think you misunderstand my reference to indigenous design. Its value (and why I refer to it) lies in its process not its product. Western/international design, as it is now, cannot last because it is based on profligate waste of diminishing materials and energy and is causing pollution and global warming. We have to understand how ‘indigenous’ design has so successfully lasted for thousands of years. How is it so efficient while at the same time nourishing generations? Then we apply our understanding of that process, along with all our technological advances, to generating our own designs which are both nourishing and practical for us now, building up our cultural identity, wherever we may be. The biggest challenge is that there are so many more of us!

Float by David Trubridge

How do you use technology, and what role do you think it plays in the future of art and design?

I use it wherever it has a role, and that is quite a lot. Of course, computers are essential to me, whether it is for doing this interview with you, for complex three-dimensional design that is impossible on paper, or for driving the machine that cuts our pieces. Also, we are trying to drive research that will lead to much more sustainable materials, and the more efficient distribution of our ideas. But it is always only a tool in my hands, and I try to never let it lead me. If the design calls for craft work, then we will do that too.

Dondola lounger by David Trubridge

After being raised in Great Britain and traveling around the world, what is it about New Zealand that made you want to call it home?

Its freshness and newness (the newest country geologically and socially), its open space both physically and metaphorically (fewer glass walls that limit creative thinking), its landscape, its distance from the industrial world, its mix of cultures, its vast oceans, and its climate.

What other artists have inspired you or expanded your way of thinking?

I am glad you say ‘artists’ not ‘designers,’ because designers have already ‘done it’ — and to be influenced by them (at least by the product, not so much the process) is to follow. Designers are sometimes called applied artists, and I see the art process as a field of research for design, whether the research is done by the designer him/herself or by a different artist. I love the sculptures of Eliasson, Deacon, Serra, Caro; the paintings of Kiefer, and contemporary women aboriginal artists such as Dorothy Napangardi. I have also been influenced by Polynesian culture, their canoes, houses, artifacts and way of seeing the world.

What are some of your favorite things, whether they directly impact your work or just make you happy?

A Napangardi painting, a Polynesian model canoe, my Macbook (I hate to admit it, but it allows me to do so much creatively, to listen to music, to read so much, to communicate so much, particularly with my family), our holiday house and its four poster bed. And just making me happy? My family, of course — Linda my partner and our two sons Sam and William.

David Trubridge